The West End has no shortage of spectacle-heavy musicals, but few lean on technical wizardry as nakedly as Back to the Future. This stage adaptation of the 1985 film is a noisy, restless machine whose strongest asset is its special effects. The DeLorean roars, the clock tower trembles, and the stage seems to liquefy into film. Without the pyrotechnics and illusions, however, the show would look thin, even amateurish, by comparison with the movie it imitates. The irony is that a story about rewriting time feels stuck in a loop.

You know the plot already. Teenager Marty McFly travels from 1985 back to 1955, accidentally attracts the affections of his own mother, and must engineer his parents’ romance in order to survive. In the film, this story balanced sharp comedy with genuine emotion. On stage, the pacing is frantic, jokes are pitched broad, and character beats are sketched so quickly they barely register before the next scene change.

Alan Silvestri and Glen Ballard’s score is the weakest link. Where the film featured Huey Lewis’s The Power of Love and Chuck Berry’s Johnny B. Goode, this production adds a suite of original songs that, to put it bluntly, rarely land. They are slickly staged but melodically bland. A handful nod towards 1950s doo-wop or 1980s pop pastiche, but they lack hooks and fail to build emotional weight. This weakness cripples the show.

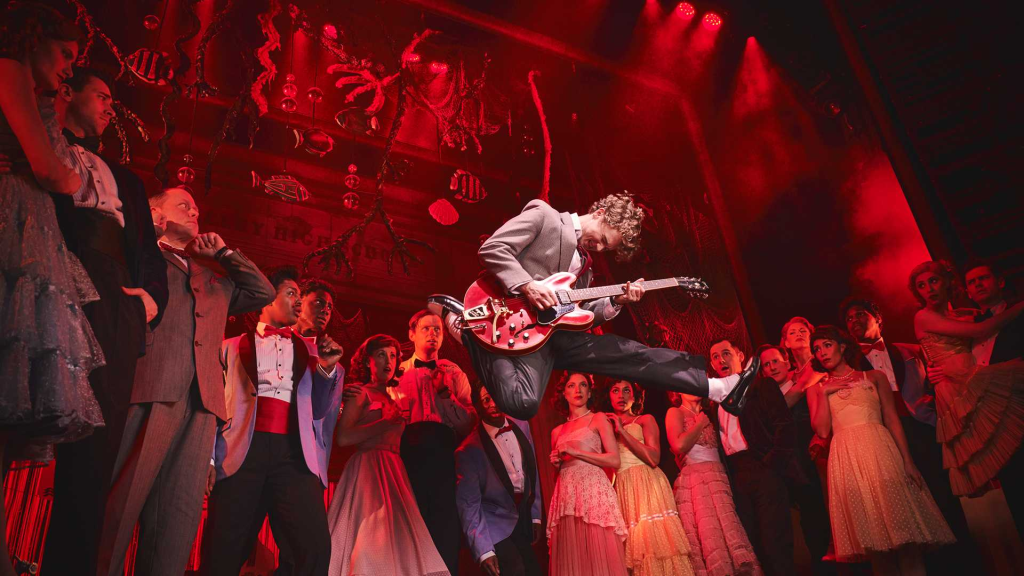

The cast work hard. Caden Brauch’s Marty is restless, bouncing around the stage with nervous energy, and he manages a wonderful tribute to Michael J Fox. Brian Conley, as Doc Brown, supplies comic eccentricity in the right places, a goggle-adjusting mad scientist with timing honed from years in musical comedy. Maddie Grace Jepson as Lorraine sings with gusto and has strong presence, though her early flirtations with Marty are played so broadly that they risk turning knowingly awkward comedy into uneasy farce. Orlando Gibbs shines as nerdy George McFly. The net effect is a company working overtime to inject warmth into material that seldom rewards them.

The design team rescue the evening. Tim Hatley’s shifting sets are slick and inventive, flipping locations in seconds and creating the illusion of cinematic jump cuts. Finn Ross’s video projections stretch the stage into an infinite canvas, while Tim Lutkin’s lighting injects velocity into nearly every moment. The much-publicised DeLorean sequences, especially the final flight at the curtain, are undeniably impressive. These effects are the show’s oxygen: they provide the rush the songs cannot. The clock-tower climax, complete with storm, cables, and vertiginous scale, is staged with enough flair to make the audience collectively gasp. These are the points where the show earns its applause.

Yet spectacle alone cannot sustain two and a half hours. Between the set-pieces, longueurs creep in. The songs pad time rather than advance story, and the humour is scattershot. Some gags land, others feel forced, and the tonal shifts from zany comedy to earnest sentiment rarely convince. Thematically, the show gestures towards nostalgia, memory, and the desire to shape one’s destiny, but it lacks the dramatic discipline to explore them. The result is a flashy but hollow entertainment that plays more like a greatest-hits tour of its source material than a reinvention.

And still, the house is full. The musical has become a commercial success. It is, frankly, something of a miracle that the production is as popular as it is. Strip away the car, projections, and lightning, and you are left with a mediocre score, thin characterisation, and an over-extended re-telling of a film that worked perfectly well without songs. Its endurance says more about the appetite for familiar brands on the West End than about theatrical quality.