James Graham’s Punch, directed by Adam Penford, arrives at the Apollo with all the subtlety of its title. It is urgent, unvarnished and at times unbearably heavy-handed. But when it connects, it hits with force.

Based on Jacob Dunne’s memoir Right From Wrong, the play traces the aftermath of a single reckless punch thrown by a nineteen-year-old that kills a paramedic. From that one act spills a narrative of grief, guilt and the slow, unglamorous pursuit of redemption.

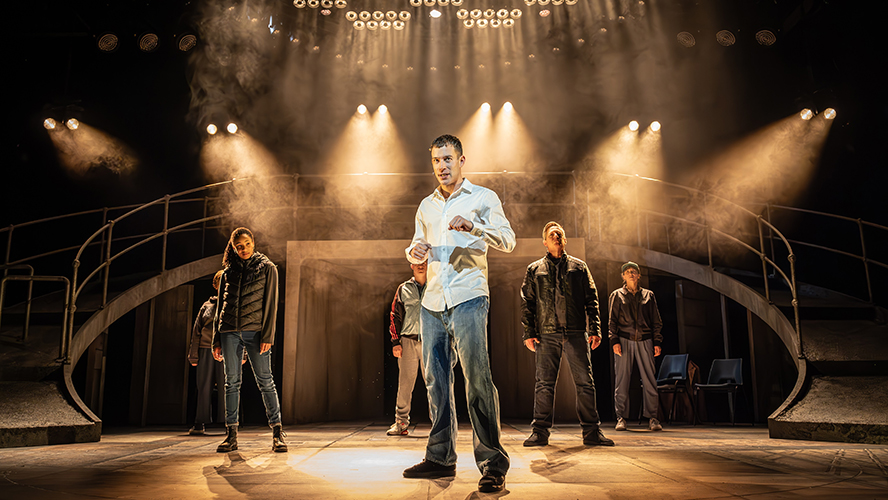

David Shields commands the stage as Jacob. He begins with defensive swagger: voice clipped, posture sharp, a mask of bravado too well-practised. By Act II the mask cracks. His pauses lengthen, his voice falters, and suddenly a half-frozen gesture speaks louder than his words. It is a meticulous unravelling, and it carries the play’s heart.

Julie Hesmondhalgh and Tony Hirst, as Joan and David, the bereaved parents, anchor the story. She holds her grief like a live wire, sparking anger at every turn; he offers bewildered dignity, softening when she edges towards rage. Their scenes together stop Punch from collapsing into a one-man portrait of guilt. In particular, an Act II confrontation (her circling fury met by his lowered, almost pleading voice) gives the play its sharpest tension.

Around them, Shalisha James-Davis plays the restorative justice facilitator with quiet precision. She does not dominate, but she alters the trajectory. A single question, delivered without ornament, tilts the whole drama off its axis. Emma Pallant and Alec Boaden add texture in supporting roles, though the script rarely allows them space to expand.

Where Graham succeeds is in forcing the audience to inhabit the messy aftermath of violence. His themes – masculinity, social neglect, the thin line between chance and catastrophe – are clear. Too clear, at times. Act I clogs with exposition and sermonising, the writing tumbling into blunt moral judgements. Transitions between Jacob’s internal monologues and external action jolt awkwardly, creating the sense of two plays uneasily stitched together. The rhythm only steadies after the interval, when characters are allowed to face one another rather than their own rhetorical flourishes.

The final scenes redeem the script’s excess. Silence becomes the most eloquent line Graham writes. A late confrontation between Jacob and the parents strips away didacticism and lets raw presence do the work. For once the play trusts its actors, and the effect is devastating.

Anna Fleischle’s design is brutalist restraint: concrete slabs, gangways, low walls. At first glance, bare. In practice, merciless. In the club scene, strobe lights and pulsing bass swallow Jacob whole, shrinking him to a corner of the stage. Later, a single cold beam isolates him on a chair, guilt incarnate. Robbie Butler’s lighting and Alexandra Faye Braithwaite’s sound refuse to stay in the background. Beats, hums and sudden noise stabs jar the senses; at times too abruptly, but the jaggedness mirrors Jacob’s own disjointed path.

The production has shed the more conspicuous devices of earlier stagings at Nottingham and the Young Vic. The Apollo version is leaner, more interior, more willing to let stillness dominate. In the West End, that restraint plays as strength.

Not every risk lands. Some viewers will bristle at the script’s tendency to underline its lessons twice. Others may find the arc too neat: the reckless boy punished, confronted, reformed, almost forgiven. But Punch does not let you slip out of discomfort. It insists you sit with the bleak possibility that redemption is not guaranteed, only scraped at.

Culturally, it lands in a raw place. The questions it raises about youth, violence and restorative justice are not academic—they hang over headlines weekly. How many lives are wrecked by a single thoughtless second? How much does society demand punishment over change? These are not new questions, but Graham ensures they sting afresh.

Punch will not soothe. It is not built to. If you want theatre that unsettles, that forces you into silence rather than applause, this is it. And if you resist its didactic edge, you may still leave with the uneasy truth it leaves behind: that human change is neither clean nor triumphant, but ragged, halting, and only ever half-won.